How Miller Lite and Bud Light’s epic clash shook the marketing world

This article is part of a four-part series about famous brand rivalries.

Few brands have the intense rivalry that Miller Lite and Bud Light have, despite Bud Light’s consistently higher sales and reach. The decades-long feud is littered with lawsuits and smear campaigns. Their aggressive back and forth has shaped beer advertising, and neither looks ready to yield as they take the battle to new fronts.

In recent years, a shrinking beer market has heightened the stakes for both brands. In 2020, the category declined 3% as hard seltzer and premium spirits started to eat into beer’s market share. While craft and import varieties generally enjoyed a pandemic boon, affordable offerings lost market share. And in an increasingly divided society, consumers may care more about social messaging and connectivity than brands squabbling over calorie and carb count. These trends could change the dynamic between Bud Light and Miller Lite going forward.

Miller basically invented the light beer category as we know it today… and Anheuser-Busch was struggling to catch up for years because Lite was so dominant.

Joel Hueston

Independent consultant

While evidence suggests beer was first brewed in 3,400 BCE, light beer is a relatively new invention. According to popular belief, the Miller Brewing Company — now a subsidiary of Molson Coors — introduced Miller Lite in 1975 as the first light, low-carb beer. Aggressive advertising fueled an instant success, helping to make light beer the powerhouse it is today. Of the top five beers in America, four of them are light: Bud Light, Coors Light, Miller Lite and Michelob Ultra make up 41.8% of the domestic beer market.

“Miller basically invented the light beer category as we know it today, when they introduced Miller Lite nationally, and Anheuser-Busch was struggling to catch up for years because Lite was so dominant,” said Joel Hueston, an independent consultant who focuses on craft breweries. He also worked for the Miller Brewing company between 1979 and 2010.

The real history of light beer is slightly different than popular belief. Miller Lite was indeed the first light beer. But it wasn’t always known as Miller Lite, and the Miller Brewing Company didn’t invent it.

Originally, Miller Lite was known as Gablinger’s Diet Beer, which was invented by biochemist Joseph L. Owades, an employee of the now-defunct Rheingold Brewing Company. Owades determined how to remove starch from beer, dramatically reducing both calories and carbs. It was meant to be the drink of choice for the health-conscious, the beer equivalent of Coca-Cola’s Tab.

After the beer failed at Rheingold, Owades got permission to share the formula with Meister Brau Brewery, where it was renamed Meister Brau Lite. That company went belly up in 1972, after which the beer was purchased by the Miller Brewing Company, then owned by tobacco behemoth Philip Morris. Three years later, the beer was reformulated and rebranded as Miller Lite and reintroduced to the world.

For years, Miller Lite was the biggest and only name in the light beer game. It leaned heavily into the “manliness” of light beer, emphasizing sports figures and celebrities in its advertising. The Miller Brewing Company also managed to market beer to those who typically don’t drink beer, and the company grew.

For most of Miller’s history, Anheuser-Busch paid little mind. To it, the bigger threat was Pabst in terms of sales. But after the Philip Morris acquisition, the beer giant began to take notice.

From a simmer to a boil

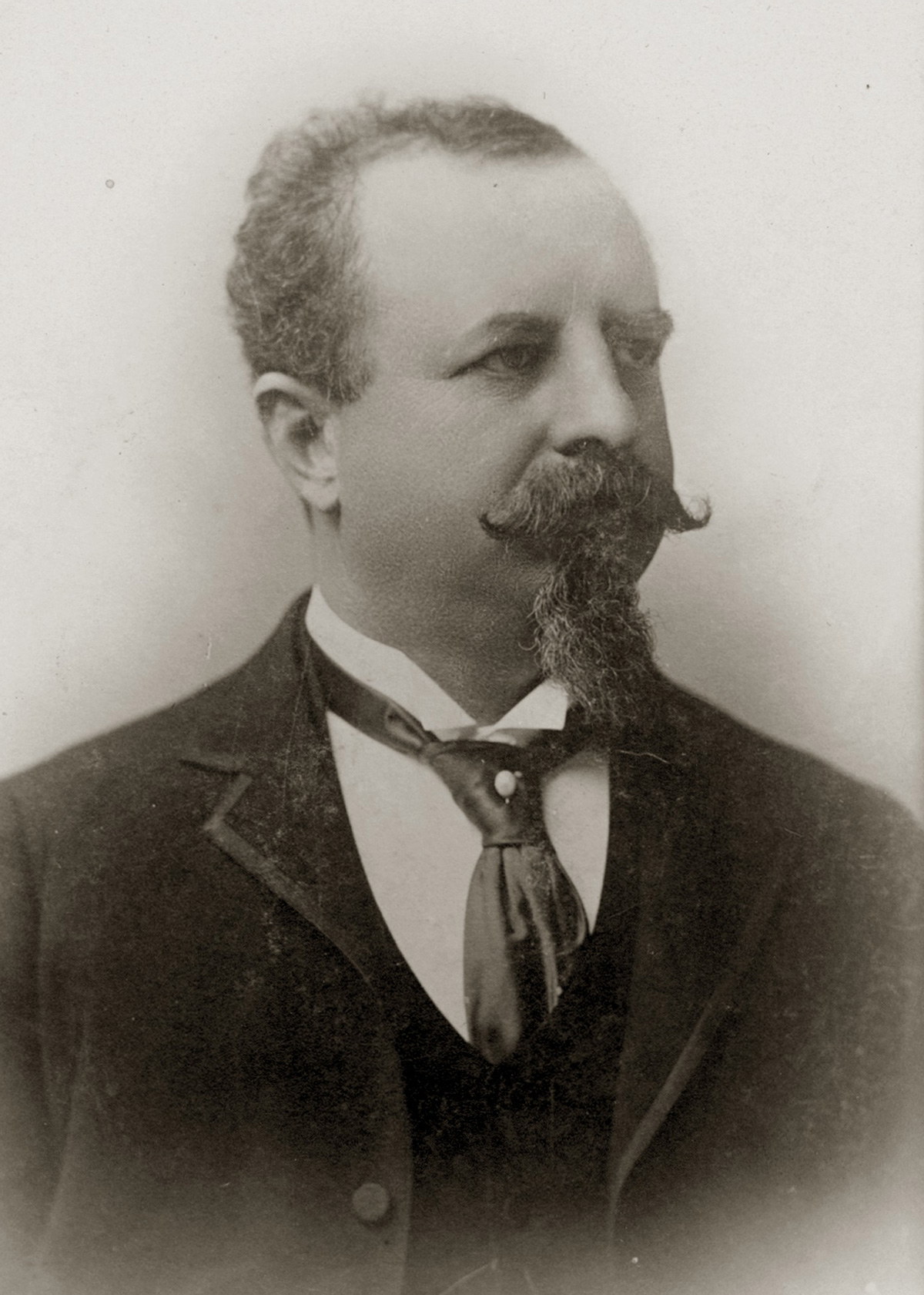

Anheuser-Busch was formed in the mid-1800s by German immigrants Eberhard Anheuser, a candle maker and Adolphus Busch, a brewery supplier. Prior to taking on Busch as a partner, Anheuser barely sold 4,000 barrels of beer a year and it reportedly tasted horrible. After marrying Anheuser’s daughter Lilly in 1861, Busch went to work for his father-in-law, according to the book “Bitter Brew: The Rise and Fall of Anheuser-Busch and America’s Kings of Beer.” By 1879, the business sold a profitable 27,000 barrels a year.

Adolphus Busch, 1890

Photographs and Print Collection/Missouri History Museum

Eberhard Anheuere, 1898

Photographs and Print Collection/Missouri History Museum

After becoming a minority partner, Busch took control of the company following Anheuser’s death and introduced a string of reforms, including purchasing the recipe for Budweiser and figuring out how to pasteurize beer, extending beer’s typically short shelf life and allowing for national sales. Anheuser-Busch expanded and quickly became the largest brewery in America, weathering Prohibition, and remains so to this day. Up until its purchase by InBev in 2008, it was family owned.

The Miller Brewing Company’s history was not as stable. While a large brewery, it was leagues away from Anheuser-Busch and was not deemed a threat. But leadership shake-ups at Anheuser-Busch threatened to shift that power balance.

The patriarch of the Anheuser-Busch family, August Anheuser “Gussie” Busch Jr. was approaching the end of a 25-year tenure as CEO in 1971. He was behind some of the company’s most memorable marketing advances, including associating the beer with baseball as owner of the St. Louis Cardinals. The now-iconic Clydesdale horses featured in Budweiser ads, such as the famous 9/11 memorial commercial, were a gift from Gussie to his father to celebrate the end of Prohibition.

By the 1970s, some employees saw Gussie and his right-hand man Richard Meyer as too traditional. Philip Morris’ purchase of the Miller Brewing Company in 1969 was evidence that the company needed to change, especially if it wanted to compete with the cigarette company’s large advertising budget.

“Philip Morris was a much more powerful company than Anheuser Busch. Their product was the No. 1 product in the world, which was Marlboro cigarettes… So [August III] thought, ‘oh my God, these guys are coming after us. We got to really go after them’, and Gussie just couldn’t be bothered with it,” William Knoedelseder, author of “Bitter Brew: The Rise and Fall of Anheuser-Busch and America’s Kings of Beer,” told Marketing Dive.

Upon Gussie’s exit in 1971, his son August A. Busch III wasn’t the one to take up the mantle. It was Meyer.

A fermenting rivalry

By the time the Miller Brewing Company had a viable product in 1973, an aggressive marketing campaign was already underway, two years before the beer went national. The Miller All Stars campaign featured retired athletes singing the praises of Miller Lite, emphasizing that it’s less filling. A now-iconic tagline first appeared during one spot: “Lite Beer from Miller: Everything you’ve always wanted in a beer… And less.” The messaging signaled that consumers could enjoy more beer. Miller Lite All Stars struck a home run, and Miller was the fourth most popular beer in America by the end of that year.

“Anheuser-Busch was very, very convinced that they should be dominating the beer business, and they weren’t when brands like Lite were doing so well,” Hueston said.

The surge of Miller Lite came at a time of great upheaval for the Anheuser-Busch family. After years of infighting, August III was installed as president in 1974. His tenure would rival that of his father’s, lasting all the way to 2002.

With new leadership, Anheuser-Busch countered Miller Lite’s growth by doubling Budweiser’s ad budget to $100 million, a number that was unheard of at the time for the company, per Knoedelseder. August III was determined to buy up every sports sponsorship possible, but there was one problem. Miller Lite had gotten there first.

“He found out that Miller, while they weren’t looking…they had gone in and acquired almost everything and there was none to be bought,” Knoedelseder said.

As Miller Lite continued to grow, Anheuser-Busch released Natural Light in 1977 and Budweiser Light in 1982. By 1994, the renamed Bud Light was the most popular beer in America, and continues to be so today.

While brand rivalry is nothing new in advertising, this particular competition continues to intensify, often using unsubstantiated claims which keep their attorneys busy.

Carolyn Hadlock

Principal, ECD Young & Laramore

Bud Light took immediate aim at Miller Lite. In 1985, Bud Light unveiled the “Give me a light” ad, in which bar patrons asked for a “light,” not specifying what they wanted. People in the bar misinterpreted the request, offering everything from a flair to a bowling ball disguised as a bomb. The patrons eventually clarified that they wanted a Bud Light. The humorous ad mocked Miller Lite’s spelling for “light” while encouraging consumers to ask for Bud Light by name.

The rivalry continued for years. However, the heat really started to turn up after the millennium.

The beer that would be king

In 2004, Miller Lite unveiled a campaign designed to respond to Bud Light’s “King of Beers” ad. In the spot, Miller Lite claimed to be the “President of Beers” and featured actor Bob Odenkrik in a faux presidential debate with a horse in a not-so-subtle reference to Budweiser’s famous draft horses.

During the ad, created by Wieden + Kennedy, Odenkrik explains that Miller Lite has fewer carbs and calories than both Bud Light and Coors Light (released in 1976) while a moderator continuously cuts him off.

To some, this is where the rivalry reached a level of intensity rarely seen in the ad industry.

“While brand rivalry is nothing new in advertising, this particular competition continues to intensify, often using unsubstantiated claims which keep their attorneys busy,” Carolyn Hadlock, principal and executive creative director at Young & Laramore, said in an email to Marketing Dive.

The campaign was a result of the fresh leadership at Miller in the form of CEO Norman Adami. He propelled the idea of taking direct shots at Anheuser-Busch via marketing, according to Hueston.

While the “President of Beers” campaign struck a chord with viewers, it more importantly motivated distributors. Independent beer distributors are an integral part of the beer supply chain. They buy the alcohol from the brewery, then sell it to stores. This way, stores don’t need to have a relationship with each brand individually, just with one wholesaler.

“It was a point in time when our distributors really needed to be fired up. And it certainly did that, the distributors love those campaigns,” Hueston said.

At the time, Anheuser-Busch controlled 50% of the domestic beer market, with supermarket sales of Bud Light totalling $1.17 billion, compared with Miller Lite’s $533.7 million. In 2002, Philip Morris offloaded the Miller Brewing Company to South African Breweries.

The aggressive “President of Beers” advertising was followed by a 13.2% sales jump, while Bud Light sales declined 0.8%. In response, Budweiser ran a full page advertisement in USA Today, saying that Miller Lite was the “Queen of Carbs” and that it was South African-owned. Miller was less than thrilled at the accusation and took Anheuser-Busch to court. But the lawsuit didn’t dissuade Anheuser-Busch, as the brand continued to take jabs at Miller’s South African ties. Anheuser-Busch ran a radio ad with the infamous Budweiser Lizards (who hadn’t been used in years) remarking how Miller couldn’t be president because it was South African-owned. One lizard even remarks, “Miller ran all those commercials for nothing.”

By 2008, Anheuser-Busch was no longer family operated after being acquired by InBev that year. The Miller Brewing Company went through its own period of upheaval. SABMiller had combined forces with Molson Coors as a joint American venture known as MillerCoors. By 2016, Molson Coors owned MillerCoors outright.

The two rival beers in 2017 would set aside their differences and unite on a bigger problem: Americans were drinking less beer.

Young U.S. consumers tend to drink less alcohol in general than older generations. When they do drink, they tend to reach for a hard seltzer, wine or spirits instead of beer. Anheuser-Busch saw a 17% drop in Bud Light sales between 2012 and 2017. Miller also saw its sales decline. In response, a number of beer companies worked with agencies to devise a campaign along the lines of the “Got Milk?” advertisements. If big beer was going to survive, they needed to work together.

But old habits die hard. Anheuser-Busch split from the pack and launched one of the brand’s most memorable campaigns.

Bud Light’s “Dilly Dilly” Super Bowl commercial in 2018.

Anheuser-Busch

Dilly Dilly!

Bud Light’s “Dilly Dilly” campaign, which debuted in late 2017 in a build-up to the 2018 Super Bowl, had all the hallmarks of a traditional Anheuser-Busch ad. It was funny, boasted memorable catchphrases and continued a long storyline involving familiar characters.

Created with Wieden + Kennedy, the campaign followed the Dilly Dilly King, played by John Hoogenakker, and his court. The series capitalized on the popular HBO series “Game of Thrones,” going so far as to collaborate on an ad where the Knight’s skull is crushed by one of the show’s characters as a dragon wreaks havoc.

In addition to playing on popular culture, several ads from the campaign also said that Miller Lite uses corn syrup in its brewing process. Corn syrup has been blamed for the obesity epidemic, and many consumers take steps to avoid it. In one spot, Bud Light delivered a giant barrel of corn syrup to Miller Lite’s castle. In another, a pair of soldiers inside a Trojan horse discuss ingredients in their beer of choice, and the Miller Lite soldier says his beer is made with corn syrup. Miller Lite was outraged about the accusation and once again took the issue to court.

Miller Lite also shot back with its own ad, showing the Dilly Dilly actors drinking Miller Lite when the cameras weren’t rolling. The lawsuit was ultimately successful, and Anheuser-Busch was required to stop mentioning corn syrup.

While clever and creative, the “Dilly Dilly” campaign came off as crass to some industry professionals.

“I, along with the rest of the world, was shocked when Budweiser did a commercial, let alone a Super Bowl ad that claimed competitor beer brands contained corn syrup. First of all, the conversation around high fructose corn syrup was 5 years old at the time and it only spurred litigation, not sales. In fact, while in 2019 case sales declined 7.1%, for the brand, Coors Light’s only decreased 3% and Miller Lite’s sales were flat,” said Young & Laramore’s Hadlock, citing Nielsen data.

Between 2018 and 2019, sales of domestic beers fell 4.6%. Despite a sales surge for inexpensive beer during the pandemic, the category was losing market share to hard seltzer and canned cocktails. A broader shift toward “premiumization” may be the nail in the light beer coffin.

Despite some claiming they can hear light beer’s death rattle, Molson Coors and Anheuser-Busch are determined to keep at it, for better or worse. Both brands have released “super light” beers in the form of Miller 64 and Bud Light Next. Additionally, the brands have attempted to meet young consumers online. Both light beers sponsor esports. Miller Lite has a contract with Complexity Gaming while Bud Light sponsors the League of Legends championship.

The next phase of the rivalry could be fought virtually in the metaverse and via NFTs. Bud Light recently unveiled a line of NFTs to promote Bud Light Next. During Super Bowl LVI, Miller Lite set up shop in the metaverse to skirt Anheuser-Busch’s monopoly on game day beer advertising.

Miller Lite’s ad for a livestreamed event on May 13, 2021, in which the company launched a can of seltzer into space.

Molson Coors

Trading hops for cannabis

Bud Light has been quick to jump on the seltzer craze. In early 2020, the brand released Bud Light Seltzer to capitalize on the trend. The effort paid off, and it’s currently the third most popular hard seltzer in America, behind White Claw and Truly.

Miller has yet to jump on the seltzer craze. While Molson Coors makes plenty of seltzer, including Vizzy, Topo Chico and the short-lived Coors Light Seltzer, Miller has refrained. If anything, it has mocked the seltzer category, including launching a can of seltzer into space. During an ad promoting the launch, an actor says, “See, we absolutely have no problem with launching a seltzer, just as long as we don’t have to brew it, or get anyone to drink it or perpetuate its existence in the physical world as we know it.”

Other alcoholic beverages may not be the only thing eating into light beer’s bottom line. Recreational cannabis is currently legal in 18 states and could start competing with beer for consumer dollars. The full extent of cannabis’s threat to the beer industry has yet to crystallize, though one thing for certain is that the beer industry is changing, and Miller Lite and Bud Light may have bigger problems than each other.

In an era when divisiveness seems pervasive, consumers may be tired of the squabbling, the vitriol and cheap shots that repeatedly culminate in legal battles.

“This rivalry feels more like a barroom brawl than an act of persuasion towards the consumer,” Hadlock said. “This personal head-to-head rivalry is an expensive conversation that is more appropriate for the boardroom. Is it really worth spending millions of dollars on the difference of 16 calories between two competitors?”